“I love language. I really like it. And I think I’d always been a little embarrassed about that and always felt that maybe I should write a bit more naturalistically in the way that people actually speak, that it was a flaw in my plays that people spoke slightly heightened poetic language. I just suddenly had this moment where I went I can’t do it. I’m obviously not good at that, and I really like words, so what I’m now going to do is I’m going to write the most words. I’m going to throw hundreds of thousands of words down and they’re going to be the most poetic words I can find, and if there’s a way of doing it that’s more heightened I’m going to do that. I’m going to hurl myself in the opposite direction. And that was the great liberation for me that resulted in a whole ream of work that I’m still doing.” — playwright David Greig

“I love language. I really like it. And I think I’d always been a little embarrassed about that and always felt that maybe I should write a bit more naturalistically in the way that people actually speak, that it was a flaw in my plays that people spoke slightly heightened poetic language. I just suddenly had this moment where I went I can’t do it. I’m obviously not good at that, and I really like words, so what I’m now going to do is I’m going to write the most words. I’m going to throw hundreds of thousands of words down and they’re going to be the most poetic words I can find, and if there’s a way of doing it that’s more heightened I’m going to do that. I’m going to hurl myself in the opposite direction. And that was the great liberation for me that resulted in a whole ream of work that I’m still doing.” — playwright David Greig

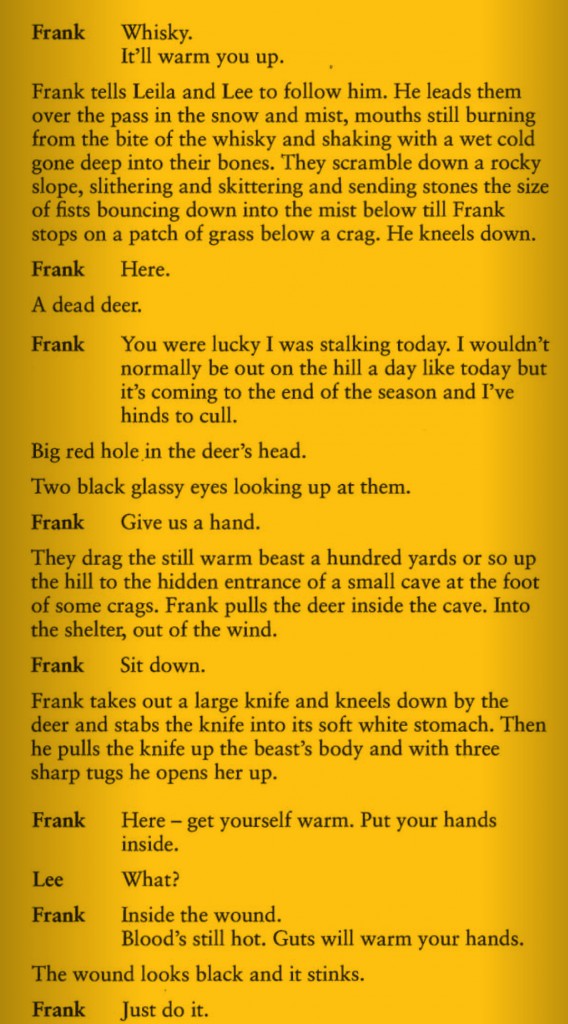

Yellow Moon was one of the first plays David Greig wrote after “the great liberation” that he describes above. The heightened language in the play is immediately apparent in the text, but something that audiences may not recognize while watching the play is how unusual David Greig’s script appears on the page. The playtext is composed mostly of narration delivered directly to the audience, written in paragraphs of prose, which are juxtaposed with sections of traditional dialogue. The dialogue is, of course, assigned to specific characters, but the playwright makes no indication of how the narration should be split up among the cast. Those decisions are left entirely up to each individual production’s director and cast. You can see a snapshot of how the text is printed above to the left.

“Greig has infused Yellow Moon with a spirit of lawlessness that is really thrilling,” says Associate Artistic Director Stuart Carden, who will direct the play for the intimate Books on Vernon stage. “There is both a dare and an invitation inherent in this way of writing. He dares you to make your own connections in the script and also invites you to take more ownership of the text by challenging you to choose how the story should be told with this specific group of actors and this unique audience. The actors and I have never met David Greig but we feel we are in a real dialogue with him because of the way he has crafted the text. It is a choice that is both anarchic and inclusive. Greig has the audacity to say, here’s a really good story, now you deal with it. There is an incredible freedom that comes with that.”

The style of the piece is similar to Travels With My Aunt which also played the bookstore space under the direction of Carden in the 2010/11 season. Both plays feature direct narration interspersed with traditional scenes. However, unlike with Yellow Moon, Travels With My Aunt adaptor Giles Havergal clearly specified which actor should play each character and which sections of the narration they should speak. Another key difference between the two plays is the identity of their narrators. In Travels with My Aunt, the four actors take turns playing Henry, the main character of the story, and the narration is always delivered from Henry’s perspective. In Yellow Moon, the storytellers are more ambiguous. When not assuming the role of a specific character, the actors have no specified identities, instead serving as a chorus to tell us the tale.

The omniscient perspective of Yellow Moon’s narrators is in keeping with the point of view of a traditional folk song, with a focus on the story that is being told instead of on the storyteller. The play is even subtitled “The Ballad of Leila and Lee”, directly alluding to the influence of oral storytelling in the writing of the piece. Yellow Moon, in a nod to Scotland’s rich history of folk music, tells a tale worthy of a traditional ballad, and does so while also using a similar style. A section in the middle of the play is even constructed in rhyming lines of verse that echoes the ballad structure: narrative written in verse and set to music.

While the structure and feel of Yellow Moon is akin to a folk ballad, the play takes its musical inspiration from another source: African American rhythm and blues. As we learn in the play, the character of Lee is named after an American folk song, “Stagger Lee,” recorded by many African American blues artists. The song is based on an event recorded in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat on December 26, 1895. Two African American friends, William Lyons and Lee Sheldon, were at a saloon drinking when an argumentative political discussion led to “Lyons snatch[ing] Sheldon’s hat from his head. The latter indignantly demanded its return. Lyons refused, and Sheldon drew his revolver and shot Lyons in the abdomen. When his victim fell to the floor, Sheldon took his hat from the hand of the wounded man and coolly walked away.” Lyons died soon after and Sheldon was arrested and convicted of the murder. The newspaper tacked onto the end of the article the odd detail that Lee Sheldon had also been known as “Stag” Lee.

Although there were five other murders in St. Louis that evening, for some reason this one resonated. Lyrics for a song concerning the event started appearing as early as 1903, and the first recordings date to 1923. The song spread across the country and the details were continually embellished and rewritten. Each song told the same core story, but the circumstances, the venue, the year, the motive and the legacy were seemingly open for interpretation. Even the name of the principal character would change from Stag Lee to Stagger Lee to Stagolee to Stack O’Lee. Famous artists to record the song include Ma Rainey, Duke Ellington, Mississippi John Hurt, James Brown, The Grateful Dead, The Clash, Nick Cave, and The Black Keys. Lloyd Price’s version of the song—which is featured in the soundscape of Yellow Moon—went to the top of the charts in 1959.

A few other R&B classics will be featured in the production, in keeping with the lasting influence of the music on Scotland and Northern England where many residents retained an affinity for soul music well into the late 70s and early 80s. Instead of popular hits of the day, however, these fans were interested in rare recordings from American soul’s heyday of the mid 60s. Record shops and DJs referred to this genre of music as Northern Soul, even though, unlike other genres, the music was neither new nor was it being created in the region it described.

“During the writing of Yellow Moon,” Greig recalls, “I was interested in the journey of black American music from Blues to Gangsta Rap and the way that the music made heroes of outlaw boys. I listened to a lot of folk music. I took a lot of walks in the forests. All of these elements found their way into the writing. I don’t research plays. My plays emerge from what I’m interested in anyway.”

No comments yet.