When asked by an interviewer about why he set Doubt in 1964, John Patrick Shanley responded that it “was a pivotal time of going from complete faith in establishments and hierarchies, to questioning those establishments and hierarchies — like the military, and organized religion. I wanted to capture something about that lost moment.”

Pope John XXIII

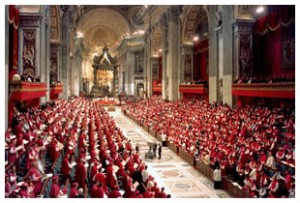

At that time, the Catholic Church, which had changed so little over the centuries, was also moving into the modern era. Pope John XXIII announced the formation of the Second Vatican Council (or Vatican II, as it was later called) in 1959, the first in almost one hundred years. Between 1962 and 1965, over two thousand bishops convened at St. Peter’s Basilica and ended up drafting 16 documents that set a new course for the church.

Second Vatican Council gathering

Religious scholar Mark S. Massa writes in his book The American Catholic Revolution: How the ‘60s Changed the Church Forever, “Most Catholics before Vatican II took it for granted that what they did on Sunday mornings looked like what the Church had always done: the sacred (if sometimes misunderstood) drama of the Mass was understood as timeless. The Mass of the Roman Rite was a ritual not only of ancient provenance, but something outside of time altogether.” Starting with Advent in 1964, Mass would now be conducted in the local language of the church, instead of Latin. Lay people would have a greater involvement in church operations and services. And the Church, which has always stood separate and withdrawn from the secular world, would play more of an active role in its outreach to the community.

Doubt occurs in the months immediately preceding the implementation of those changes. The instructions from the Vatican, however, would already have been communicated internally and the priests and nuns were aware of and grappling with the changes to their lives and professions. “For the first time in their history,” writes Massa, “Catholics now addressed how ‘relevant’ their religious symbols and worship should be. Questions of what Eucharist and prayer actually meant were presented as real, live issues that could be debated in print and at public meetings. The forces of modernity, so long held at bay outside the strong fortress of the Church, now pounded at the door and demanded attention.” The instability caused by such questioning bred discontent between those enthusiastic about the reforms and those who preferred the old way.

What did not change was the strict hierarchy of roles within the Church. Women were still only allowed to be nuns, one of the lowest levels of the church’s leadership structure. They were required to report to priests and bishops, men who were higher in the structure. In the case of the abuse scandal, this chain of command contributed to the mishandling of the response to many cases. “This had to create very powerful frustrations and moral dilemmas for these women,” Shanley acknowledged in a 2004 interview with American Theatre. “Because nuns were the ones who were noticing the children with aberrant behavior, distressed children, falling grades, and in some cases they had to be the ones who discovered what was happening.”

Sisters of Charity in NY

“Walking around the Bronx in 1964,” Shanley recalled to an interviewer in 2008, “you’d see nuns in their bonnets and habits, but you didn’t realize that within just a few years, they wouldn’t be wearing them anymore and that time would be gone forever. Father Flynn is very much a product of the early 1960s in the way he is questioning institutions as they stand, while still working within the system. He wants to make the church that he loves viable in a changing world.”

Herman Badillo

American cities were also experiencing profound change. The era of “white flight” was in full swing, with middle-class white families relocating to the newly developed suburbs and lower-income black and Latino families moving into the inner-city neighborhoods that were being abandoned. The Bronx had historically been populated by European immigrant groups, such as the Irish, Italians, Poles and Russians. Between 1960 and 1970, the white population of the Bronx fell from 1.1 million to less than 800,000, while both the black and Latino (mostly Puerto Rican) populations doubled to between 300,000 and 400,000 each. In 1965, Herman Badillo became the first Puerto Rican to be elected borough president. The church, schools and other institutions were forced to adjust to the changing ethnic and economic makeup of the neighborhood.

In the preface to the published edition of Doubt: A Parable, John Patrick Shanley reflects on the 1960s and where our society is now:

“I have never forgotten the lessons of that era, nor learned them well enough. I still long for a shared certainty, an assumption of safety, the reassurance of believing that others know better than me what’s for the best. But I have been led by the bitter necessities of an interesting life to value that age-old practice of the wise: Doubt.

We are living in a culture of extreme advocacy, of confrontation, of judgment, and of verdict. Discussion has given way to debate. Communication has become a contest of wills. Public talking has become obnoxious and insincere. Why? Maybe it’s because deep down under the chatter we have come to a place where we know that we don’t know…anything. But nobody’s willing to say that.

Doubt requires more courage than conviction does, and more energy; because conviction is a resting place and doubt is infinite–it is a passionate exercise. You may come out of my play uncertain. You may want to be sure. Look down on that feeling. We’ve got to learn to live with a full measure of uncertainty. There is no last word. That’s the silence under the chatter of our time.” ■

More on Doubt: A Parable:

Articles | Videos | Production Details | Tickets

No comments yet.