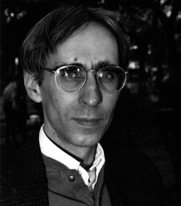

David Ives, renowned playwright and translator/adaptor of The Liar, answers some of our questions about his influences, career and approach to writing.

Bobby Kennedy, Writers’ Theatre‘s Producing and Literary Associate: You were born and grew up in Chicago, attending Northwestern University for undergrad. Any fond memories to share from your time here?

David Ives: I was standing out on the end of the jetty below the old astronomical Observatory around 2:00am on a frigid winter night. The lake was frozen into white blocks in front of me; the sky was black. From above and behind me I heard: “Beautiful, isn’t it.” Standing on the Observatory‘s walkway was NU’s famous Professor J. Allen Hynek, enjoying the sky in person that he was studying inside the tower. “Want to come up?” he said, and let me in to look at the stars through the big telescope. It was a scene that felt symbolic even at the moment it was happening.

BK: At what point did you decide you wanted to be a playwright? What led to that realization?

David Ives: I wrote my first play when I was nine or ten, but really knew I wanted to write for the theatre when I was 17 and saw a matinee of A Delicate Balance at Chicago’s Studebaker Theatre with Hume Cronyn and Jessica Tandy. An indelible afternoon. Life-changing, literally.

BK: Earlier in your career you were drawn to writing shorter plays, but you have been working more on full-length plays and musicals in recent years. Was there a reason you started with the former and progressed to the latter?

David Ives: I don’t think one ever “progresses” in the arts, one just does one’s work and wrestles with whatever’s on one’s chest at any particular time. In fact I didn’t begin with short comedies but actually began with long complicated serious plays for casts of 20 people that nobody much knew about but that were very important to me at the time. You might even say that these longer pieces I’ve been doing lately are a “regression” from the short plays, given how demanding the short play form is. Anybody can splash out 90 or 100 minutes of rebarbative dialogue. A good sharp ten-minute play is as challenging as a 32-bar Broadway song or a two-minute-and-twenty-five second Louis Armstrong masterpiece. A good sentence can be challenging some days, and a “progression” from pages and pages of blather.

BK: Do you derive more pleasure from your original works or your “translaptations”?

David Ives: I take pleasure in everything I write or else I stop work immediately. I also have to say I don’t draw a line between “original” work and “translaptation.” Corneille was “translaptating” a Spanish original when he wrote The Liar and being very original about it, too. I was just following Corneille’s example, and made The Liar into something rather different even though it’s recognizably the same plot as Corneille’s. Shakespeare was “translaptating” other people in 35 of his 37 plays. Would we say Hamlet or Lear or Romeo and Juliet aren’t “original”? In fact I would bet that if you ran into Shakespeare outside the Globe and asked him his profession, he probably would have said: “Adapter.” Or possibly “capitalist producer.”

BK: Your play, Venus in Fur, while an original work, draws upon the novel of the same name. Do you usually look for some sort of a source material? Or are there certain subjects you feel passionate about?

David Ives: I like drawing on something pre-existing because plot is hard for me. If somebody else can hand me the lineaments of a story and I can proceed from there, so much the better as far as I’m concerned. As for subjects I feel passionate about, they’re the same subjects playwrights have been interested in since Aeschylus 2,500 years ago: life, birth, death, sex, politics, religion, why women are wise and men foolish or vice versa, and what makes people laugh or cry and why. And, of course, the nature of existence and how to sell tickets to it during snowstorms.

No comments yet.