Anne Frank has been called “a symbol for the lost promise of the children who died in the Holocaust.”

Anne Frank has been called “a symbol for the lost promise of the children who died in the Holocaust.”

Out of the many artists who have died too soon, the Jewish teen is one whose stolen future is pondered the most. Equally worthy of exploration, however, is the question of how this young girl came to be a symbol of the 20th century’s darkest hour in the first place.

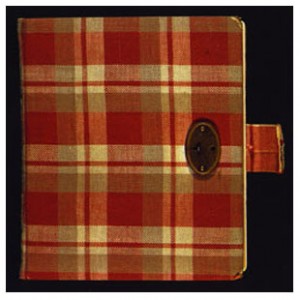

On June 12, 1942, Anne Frank was given a small autograph book by her parents for her thirteenth birthday. She decided to instead use the book as a diary and almost immediately began documenting her life in her adopted home of Amsterdam. Her father, Otto Frank, left their hometown of Frankfurt, Germany, in 1933 to start a new business in the Netherlands, and the rest of the Frank family followed in 1934.Germany invaded the Netherlands in May 1940 and soon implemented the same discriminatory policies already in effect in other Nazi-controlled countries. Anne and her older sister Margot had to withdraw from their schools and enroll in a school for Jews only. Otto transferred his ownership shares of his two companies to Dutch co-workers so that the companies wouldn’t be shut down.

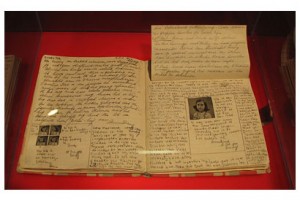

Otto was already planning to take his family into hiding, but the plan had to be accelerated when Margot received a communication from the government ordering her to report for relocation to a work camp. On the morning of July 6, 1942—less than a month after receiving her diary—Anne and her family moved into a secret annex above the offices of Otto’s workplace. With the help of a few trusted Dutch citizens they, along with several others, would remain hidden here for a little over two years. What transpired in the secret annex over that period of time is chronicled by the teenage Anne in the pages of her diary.

Amsterdam was historically referred to as the Jerusalem of the West due to its history of religious tolerance and support of the local Jewish community. There were more than 140,000 Jews in the Netherlands in 1940, including around 25,000 who had fled Germany like the Franks. Horrifically, only 35,000 Dutch Jews (25%) survived, the highest death toll of any western European country. Many factors contributed to this. The Netherlands was the most densely inhabited country in Western Europe, making it far more difficult for Jews to escape or hide. The Dutch government had also kept meticulous records about all of its citizens, including religious status, to which the Nazis gained access.

Broadcasting from London in 1944, Dutch Education Minister Gerrit Bolkestein implored his people to put their experiences during the occupation into writing. “History cannot be written on the basis of official decisions and documents alone. If our descendants are to understand fully what we as a nation have had to endure and overcome during these years, then what we really need are ordinary documents—a diary, letters.”

Many of those persecuted or killed in the Holocaust—in all parts of Europe, not just the Netherlands—documented their experiences, either in the moment or after the war was over. The United States Holocaust Museum in Washington, DC has a library full of first-hand accounts; Amazon.com has hundreds for sale as well.

So the question is: why this diary? Out of all the writings of the millions of Jews who lived through or died during the Holocaust, why did the diary kept by Anne Frank become the key literary document of the 20th century’s greatest tragedy?

There is no definitive answer, of course. There rarely is. In this case, one key element seems to be the need for a personal connection to this tragedy. Human psychology isn’t wired to allow a true comprehension of genocide. We understand what it is like to lose people we know, but grasping the notion of 6 million human beings having been systematically executed is not something evolutionary biology has equipped us with. Experiencing the loss of one of those people through fully realized artistic expression gives humanity to a statistic and a basis on which to take in the scale of the destruction.

Adding to this is the hope and optimism that Anne expresses throughout her diary. Even as her life was unknowingly almost at an end, she retains what strikes us as an astonishing degree of positivity. Even as it put a face to the monumental tragedy of the Holocaust, Anne’s story has also served as an affirmation of the good in humanity and an inspiration to a world desperately struggling to find a way forward.

But most of all it is Anne’s writing that justifies the acclaim. This diary she had been keeping could be more than just a depository for her thoughts; it could be a primary document that might be read by everyone. With that goal in mind, she began to edit and rewrite her entries into something with higher aspirations. Four months later, the family was arrested. That Anne, at fourteen years old, had the vision and ability to craft one of the most moving works of all time is proof of the lost promise of this gifted young writer. Instead of a diary, the book became literature, and instead of obscurity, Anne achieved greatness. ■

More on The Diary of Anne Frank:

Articles | Videos | Production Details | Tickets

No comments yet.