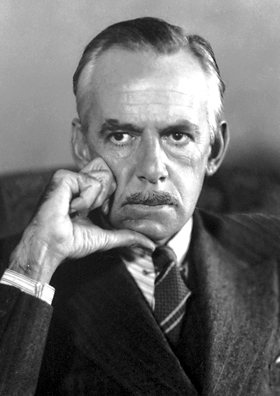

Eugene O’Neill was the first truly great American dramatist.

Eugene O’Neill in the mid-1930s.

His innovations changed the way drama was thought about in America by introducing several radical conventions of modern theater. His use of honest and naturalistic American vernacular and his depiction of true-to-life characters from marginalized backgrounds brought a realism to the American stage that hadn’t been seen before. These innovations paved the way for the mid-20th century golden era of great American drama by the likes of Lillian Hellman, Thornton Wilder, Tennessee Williams, Arthur Miller and others.

O’Neill was born in 1888 in New York City to James and Ella O’Neill. He was the third of their children, after Jamie O’Neill and Edmund O’Neill, the latter of whom died as an infant before Eugene was born. Perhaps predictably, from a very young age, the future playwright maintained a dismal view of life. He was enrolled in Catholic school, but this did not last more than a few years. O’Neill chose to switch to a secular school, and along with this academic change came increasing rebellion and nihilism. He went on to attend Princeton University for only a brief time. Accounts vary as to the reason for his premature departure from the institution, but many suggest that he was dismissed from the school for bad behavior, missing classes, excessive drinking and bringing prostitutes to campus. Aside from attending a playwriting class later on at Harvard, he never went back to finish his formal education.

Studio black-and-white portrait of playwright Eugene O’Neill as a child. Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Following the turmoil of his youth, O’Neill tried his hand at several careers, including working as a seaman on steamer ships and writing as a journalist for The Telegraph. He had three troubled marriages over the course of his adult life, the first of which was to Kathleen Jenkins. It was brief, just long enough for him to have a son, Eugene O’Neill, Jr., and the marriage ultimately ended in divorce. It was after this, in late 1911, that O’Neill made a suicide attempt. Shortly following, in 1912 he was diagnosed with a mild case of tuberculosis and spent six months in a sanatorium recovering. During this recovery period, O’Neill had time to reflect on his life and his goals, and chose to launch himself headlong into playwriting. Here was the emergence of the theater artist who would eventually, after Shakespeare and Shaw, become the most extensively produced dramatist in the USA and abroad.

O’Neill’s earliest plays were put on by a very small theatre group known as the Provincetown Players, and they were based on the two years he spent working as a seaman. The series of one-acts was called the SS Glencairn Cycle, and included the plays Bound East for Cardiff, The Long Voyage Home, In the Zone, Moon of the Carribbees and several others. These one-acts were full of realistic seafaring figures, speaking in recognizable American dialogue, and they pushed O’Neill quickly ahead into his first successful period as a professional writer.

Photograph of Pauline Lord as Anna Christopherson, James T. Mack as Johnny-the-Priest and Eugenie Blair as Marthy Owen in the original Broadway production of Anna Christie (1921). Public domain.

Now a full-time playwright and author of several full-length plays, Eugene O’Neill won the Pulitzer Prize three times in his early career for Beyond the Horizon (1920), Anna Christie (1922) and Strange Interlude (1928). Other famous plays he wrote in this period of success included The Hairy Ape (1922), Desire Under the Elms (1922), Mourning Becomes Electra (1931) and Ah, Wilderness! (1933). These plays were a series of stirring tragedies bringing new conventions to the modern American stage, using techniques and tropes of Greek drama to write about characters of the present world. Ah, Wilderness!, on the other hand, was one of only a few comedies O’Neill would write, based on his own imagined, idealized childhood. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1936—the first American playwright to do so.

O’Neill’s body of work consistently involves themes of death and mourning as a result of the sadness he sustained throughout his life. Many of his friends died when he was young, a majority from suicide, in a short period between 1913 and 1919. He also dealt with the deaths of his close family members in a remarkably short period, losing his mother, father and brother between 1920 and 1923. Although O’Neill did not deal well with the loss of his parents, Eugene’s older brother Jamie was far less able to cope and plunged headlong into destructive alcoholism and died at age 45.

Eugene, Jamie and James O’Neill on the porch of the Monte Cristo Cottage, c. 1900. Public domain.

From this period of loss onward, O’Neill’s writing was part of a long process of grieving and mourning. The playwright wrote his deceased family members into multiple plays, putting their stories on stage and attempting to offer himself some closure in the process. Jamie O’Neill appears more often than anyone else, including a significant appearance in A Moon for the Misbegotten.

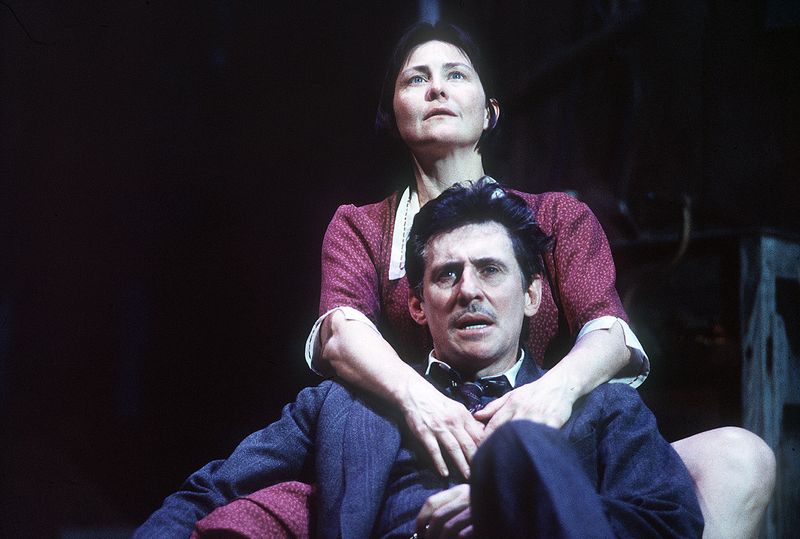

The character James Tyrone, Jr. in Moon is a deliberate and direct representation of Jamie O’Neill. Many of the incidents Jim describes in the play, such as excessive drinking habits and extensive, salacious histories with women, were also true to Jamie’s life. Josie Hogan, the protagonist of A Moon for the Misbegotten, sees Jim Tyrone as Eugene O’Neill saw Jamie O’Neill in many ways, and the themes of mourning and forgiveness within the play connect deeply to O’Neill’s desire to absolve his brother of guilt, even after his death.

Photograph of Cherry Jones as Josie Hogan and Gabriel Byrne as James Tyrone, Jr. in the Broadway revival production of A Moon for the Misbegotten (2000). Photo by Eric Y. Exit.

Many of O’Neill’s most famous plays were written in the last phase of his work, although these plays were not as fully appreciated or admired during O’Neill’s lifetime. Numerous modern critics say that the plays he wrote after winning the Nobel Prize were, in fact, his best. Long Day’s Journey Into Night, for example, written in 1941, is O’Neill’s most famous play. However, it was not published until after O’Neill’s death due to his desire to protect his privacy, as the play details the lives of the O’Neill family with great specificity. The Iceman Cometh, another famous title, was performed in 1945 on Broadway, the last Broadway opening of O’Neill’s lifetime. Lastly, A Moon for the Misbegotten was the final play O’Neill ever saw produced, in 1946. These last three plays are all intensely autobiographical and are still known as some of his greatest successes.

O’Neill was unable to write for many of the last years of his life due to a general state of neurological unwellness, as well as a tremor in his hand. He died of pneumonia in 1953, leaving behind a legacy of over 50 plays. His work continued to inspire audiences immediately after his death. When Long Day’s Journey into Night was finally performed for the first time on Broadway in 1957, it received a Tony Award and posthumously gave O’Neill a fourth Pulitzer Prize.

O’Neill often spoke about the desire to “place [his plays] directly from his imagination into the imagination of the reader.” His plays are read widely by Americans still, entering the imaginations of those who read for pleasure as well as theatre-makers who then bring his words to life. Through them, the works of Eugene O’Neill provide insight into the great sadnesses of his life but also serve as a reminder of O’Neill’s attempts to forgive himself and the members of his family—“all four haunted Tyrones,” as he wrote about Long Day’s Journey Into Night. His works remain some of the most celebrated plays in the American dramatic canon.

No comments yet.