Theresa Rebeck’s play The Scene opens at a party in a New York City home with two men and one woman in conversation. It quickly becomes clear that the men have made assumptions about this woman based on her age, looks, speech and behavior. The woman, Clea, is younger and new to the city, trying to find her way into the entertainment industry. One of the men, Charlie, is an actor in his 40s who is now struggling to find work. As the play unfolds, audiences witness how that initial interaction leads to enormous consequences for everyone involved.

The premise of The Scene is worth summarizing here, because it captures two important themes that resonate in the play and in our current moment: how women act in a society that, despite progress towards equality, is still largely run by men, and how men cope with having their dominance chipped away at with each passing year.

In her book, Enlightened Sexism: The Seductive Message that Feminism’s Work is Done, cultural critic Susan J. Douglas explores the disconnect between media representations of gender equality and the real-world situation:

“If you immerse yourself in the media fare of the past ten to fifteen years, what you see is a rather large gap between how the vast majority of girls and women live their lives, and what they see—and don’t see—in the media. Ironically, it is just the opposite of the gap in the 1950s and ‘60s. Back then the media illusion was that the aspirations of girls and women weren’t changing at all when they were. Now, the media illusion is that equality for girls and women is an accomplished fact when it isn’t. Then the media were behind the curve; now, ironically, they’re ahead.”

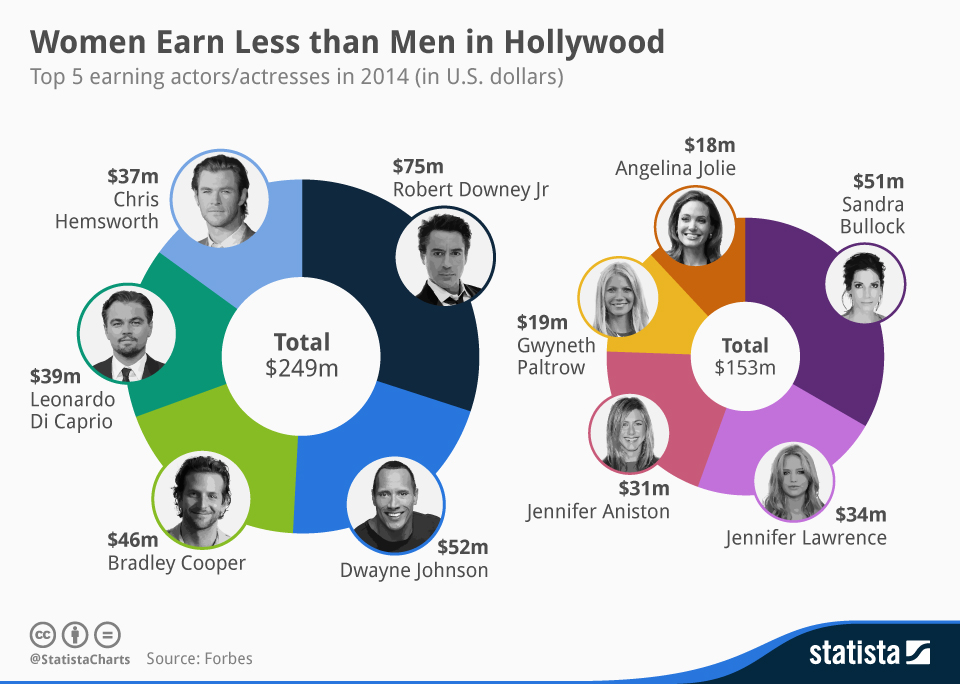

Despite the proliferation of women in roles of power on TV and in film, the top three occupations for women remain secretaries and administrative assistants, elementary and middle school teachers and registered nurses, according to 2014 statistics from the US Department of Labor. Meanwhile, women make up only 27.9% of CEOs, 24.7% of computer and mathematical occupations, 15.1% of architecture and engineering occupations and 34.5% of lawyers. The gender pay gap also persists, with women earning only 80% of what men in the same field earn. Women of color have it even worse, with black women making only 63% and Latino women 54% of what a white man in their field earns.

So why is equality presented as the status quo in the media when the reality remains so skewed? And how does a new era of achieved feminism coexist with the popularity of regressive depictions of male/female relations as in The Bachelor? The reality is that, as the principles of feminism have become mainstream, attitudes of sexism have had to mask their intent, as Douglas further explains:

“Enlightened sexism […] insists that women have made plenty of progress because of feminism—indeed, full equality has allegedly been achieved—so now it’s okay, even amusing, to resurrect sexist stereotypes of girls and women. After all, these images can’t possibly undermine women’s equality at this late date, right? More to the point, enlightened sexism sells the line that it is precisely through women’s calculated deployment of their faces, bodies, attire, and sexuality that they gain and enjoy true power—power that is fun, that men will not resent, and indeed will embrace. True power here has nothing to do with economic independence or professional achievement (that’s a given): it has to do with getting men to lust after you and other women to envy you. […] The fantasies laid before us, in their various forms, school us in how to forge a perfect and allegedly empowering compromise between feminism and femininity. And that compromise insists that women strike a bargain. We can play sports, excel at school, go to college, aspire to—and get—jobs previously reserved for men, be working mothers, and so forth. But in exchange, we must obsess about our faces, weight, breast size, clothing brands, decorating, perfectly calibrated child-rearing, about pleasing men and being envied by other women.”

Pictured: Women Strike for Peace at the Women’s Strike for Equality Demonstration in New York, 1970. Photo by Eugene Gordon/The New York Historical Society/Getty Images.

Both Clea and Charlie’s wife, Stella, are trying to navigate an entertainment industry where women represent only 36.9% of producers and directors. These women from different backgrounds and at different stages of their lives must navigate the same challenges but choose to do so in distinct ways. While Stella has worked hard to rise to her current position in a male-dominated workplace—or “acted above [her] Sex” as philosophers in the 18th century called it—Clea looks to be taking an approach influenced by the media depictions that Douglas has termed “enlightened sexism.” But, as we find out in the play, the truth is that things aren’t always as they appear.

Much is changing, however, and any change to the status quo can be perceived as a threat to the traditional holders of power: men. In 2010, “for the first time in American history, the balance of the workforce tipped toward women, who [for several months held] a majority of the nation’s jobs,” noted Hanna Rosin in a cover story for The Atlantic entitled “The End of Men.” Rosin writes, “The working class, which has long defined our notions of masculinity, is slowly turning into a matriarchy, with men increasingly absent from the home and women making all the decisions. Women dominate today’s colleges and professional schools—for every two men who will receive a B.A. this year, three women will do the same. Of the 15 job categories projected to grow the most in the next decade in the U.S., all but two are occupied primarily by women.”

Sociologist Michael Kimmel, in his book Angry White Men: American Masculinity at the End of an Era, further explores the changing gender dynamics of the 21st century and how progress toward equality has unmoored the traditional male societal advantages:

“It’s not the end of the era of ‘men.’ […] It’s the end of the era of men’s entitlement, the era in which a young man could assume, without question, it was not only ‘a man’s world’ but a straight white man’s world. It is less of a man’s world, today, that’s true—white men have to share some space with others. But it is no longer a world of unquestioned male privilege. Men may still be ‘in power,’ and many men may not feel powerful, but it is the sense of entitlement—that sense that although I may not be in the power at the moment, I deserve to be, and if I’m not, something is definitely wrong—that is coming to an end. It is a world of diminished expectations for all white men, who have benefited from an unequal system for so long.”

In The Scene, Charlie has reached a point in his acting career where work is not coming as frequently and as easily as it once did. There is a part in a TV pilot that might be available to him, but he will have to ask for it, something he can’t bring himself to do. By failing to adjust his expectations of and approach to life in a new era where the playing field is more level than it has ever been, Charlie grows resentful of his perceived lack of opportunity and success, and that resentment begins to boil over as the events of the play unfold.

All of this information serves as a useful snapshot to illustrate where things stand for men and women at this point in history. While there are no sociology lectures or charts of statistics on the inequality of the sexes included in the play, these larger societal trends have as much influence on Clea, Charlie and Stella as they do on all American men and women living today

No comments yet.